Risk Ledger’s recently-released Data Insights Report on the state of cybersecurity in the supply chain found that 40% of third-party suppliers do not conduct regular penetration tests of internal systems.

Moreover, the research found that 32% do not have a supplier security policy that outlines the security requirements that their suppliers should meet – putting their own data, as well as that of their customers, at risk.

Following the release of the report, we took the time to ask Emily Hoges, Chief of Staff at Risk Ledger, about the conclusions of the research, as well as learn what companies across the supply chain can do to minimise cybersecurity risk as digitalisation and data sharing become ever more commonplace.

Thanks for joining us Emily. To what extent has the rapid pace of digitalisation in the supply chain during the pandemic increased cybersecurity risk?

The rise of digitalisation has contributed towards the increase in cyber attacks through the supply chain over the last few years. The move towards automation is a good thing for the industry and helps businesses enhance productivity and progress. Like you said, the pandemic accelerated this process.

However, because it was an emergency situation for a lot of businesses, some of the usual processes had to go out the window in order to ensure business continuity. Naturally, when you’re in that emergency situation, you have to do what it takes to keep your business moving. The pandemic thus opened up opportunities for attackers to maliciously exploit some of the vulnerabilities that opened up.

So a business may have had to move from manual based processes to some kind of automated solution in a way that was more rushed than it would normally have been. The same could be true with regard to the onboarding of a supplier, the decision of which supplier to choose in the first place, or even the integration of some systems.

What we see now is a situation where a lot of businesses are trying to play catch up. They’re almost cleaning up some of those risks that were introduced through the pandemic period. Companies are putting a lot more attention on their supply chain and the risk associated with their suppliers.

Of course, this is not always easy to do, it’s much easier to do it in the first place when you’re first onboarding the suppliers, but because of what had happened, that wasn’t possible.

This is one of the factors contributing to why we’re seeing an increase in supply chain attacks and why it’s so important now for businesses to take that step back and look at their supply chain, and figure out how they’re going to manage it going forward.

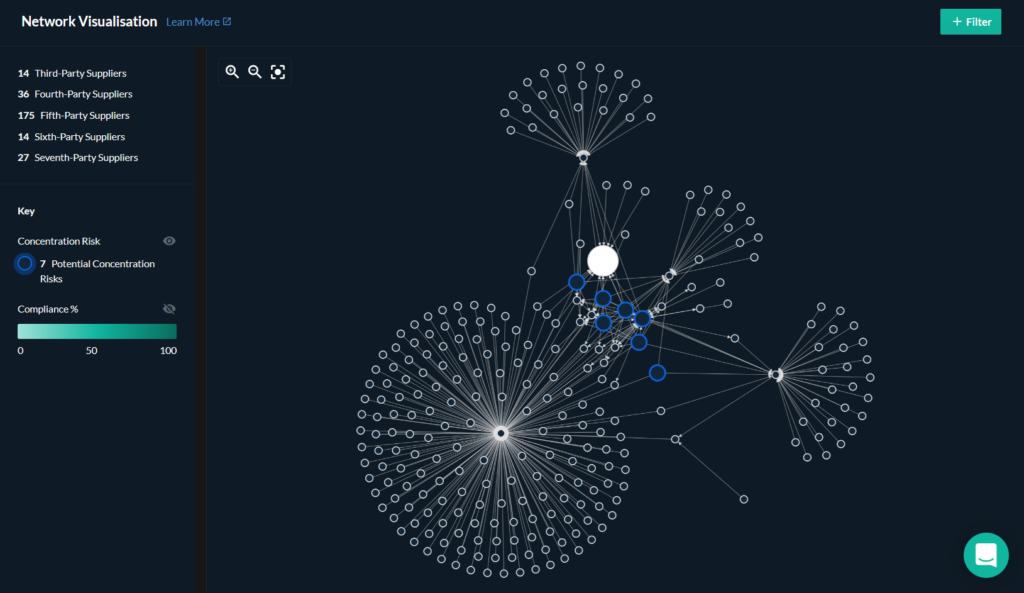

Photo: Risk Ledger

The supply chain is full of different players of various shapes and sizes. What should companies expect of one another with regards to ensuring that their digital interactions are as secure as they can be?

The most important thing here is the transparency and cooperation between the two organisations.

It’s not just the responsibility of the supplier to share information and be transparent. There’s also a responsibility on the customer business at the top of the supply chain to create and foster a relationship that enables that transparency.

One of the big problems with supplier due diligence, supplier assurance and third party risk management at the moment is that most organisations take an audit / assessment approach whereby a supplier who’s trying to win a contract and wants to do business with an organisation is faced with what feels like an exam or a test.

Naturally, you’re going to want to pass that test. So suppliers are put under this huge pressure to give the right answers, to say the right things, and to make sure they get that commercial relationship.

The need for transparency and collaboration must be something that people on both sides sign up to and agree on. They’re going to need to work collaboratively, so that the organisation at the top of the supply chain can have visibility of exactly what the vulnerabilities are.

What are the things that could go wrong with this supplier? Also, as the suppliers are not at fault in a lot of cases, in what other ways may the organisation be vulnerable to attack? The way we effectively manage that cyber risk is by understanding those vulnerabilities, getting in front of them and putting mitigations in place.

What’s happening at the moment is that there isn’t always that honesty and transparency because there’s a commercial relationship at stake. So there’s a shift in the way in which we approach the relationship needed to enable the business at the top to properly assess and understand the risk that’s that they’re exposed to.

Therefore, it’s important to put the mitigating options in place, and also for the supplier to be honest with the customer, so they can support each other.

It might be that the end customer at the top of the supply chain is much more mature and has much more resources and expertise available to them. They might be able to support that supplier with some of their cyber defences.

However, they can’t get to that point unless there’s been an open, honest conversation about what those weaknesses might be. The same thing applies to the understanding of the weaknesses further down the supply chain.

At the moment, very few organisations know much about their broader supply chain beyond their immediate third parties. Even when they may have some understanding about it from a logistical perspective, they might not necessarily know what kind of cybersecurity risks there might be until there’s an incident or a breach. Then, suddenly, it’s revealed exactly what happened – where the data was taken from and where the attacker first infiltrated that supply chain.

So there’s a whole ecosystem here in which everybody involved in the chain can work together to ensure every link in that chain is as secure as it can be.

Moreover, aligning the legal, contractual and sales conversations that happen can foster improvements and enhanced security all the way down the chain.

Photo: Risk Ledger

Looking at the figures in the report, a number of the cybersecurity shortcomings appear surprising. Is it the case that the risk-reward equation is at play here? Are the benefits of accelerating digital cooperation or having access to more suppliers or shippers arguably too tempting for some companies, and hence some security issues may be overlooked?

Well, you’ve got to be careful with being too prescriptive about what a business should do when it comes to risk and security. Everything we’re talking about here is all about risk. Risk is always going to be a balancing act between what you’re willing to accept and what you’re not. Any business has to accept a level of risk, otherwise, they can’t do business.

When we talk about cybersecurity risks, you could choose not to use any digital systems at all, to reduce your cyber risk to almost zero. But of course, you can’t do business in that way – you’re not going to survive as a company.

There’s always that balancing act between avoiding risk and progressing or innovating. Companies need to choose how to deploy their limited resources. For example, they might have to make a decision between putting CCTV cameras up in one of their buildings or encrypting their laptops to secure the data on them. In an ideal world, you’d do all of those things, but nobody has unlimited time and resources.

Companies have to make decisions about what they do and what they don’t do. The right answers will depend entirely on their business context, what type of data they hold, what kind of operations they do, what people they have, and the way they work and the locations in which they work.

In the context of the customer organisation and the service or the relationship they have with that supplier, they will need to determine whether the fact their supplier does not have CCTV cameras is a deal breaker or not. Is it something that I can accept in this situation?

The report focused on cybersecurity. Are there nonetheless cases whereby physical security lapses can increase cybersecurity risks?

Yes, physical security issues can overlap with cybersecurity. If we want to mitigate cybersecurity risks, physical security also becomes important because a cyber attack can start from a physical entry point or a people-related vulnerability.

It might be that somebody socially engineers their way into a building. Then, once they’re in the building, they can access the Wi-Fi and perhaps the corporate network, or they might even get physical access to a machine, a server or another endpoint from which they could launch a cyber attack.

It’s hard to say whether physical controls are being almost usurped by the cyber controls. I don’t think they’re necessarily intertwined in that way. In some cases, budgets and teams which manage cyber risk versus physical risks may be entirely separate.

In some businesses they may need to work much more closely together, and might even have joint budgets and joint decisions. In this case it can be worth tracking the risk pathway or the event that they’re trying to prevent from crossing from the physical into the cyber world.

What we don’t cover in this report is the wider physical security and other physical risks that come from either having or not having physical controls in place.

To what extent will the findings of the report influence your work?

It hasn’t changed the way in which we go about our business. The Risk Ledger platform enables organisations to share data with their customers and obtain data from their suppliers, as well as their suppliers further down the chain.

What we want to do is to encourage a bit more transparency and honest conversation between organisations and their suppliers. By reporting this kind of data, we are just highlighting the accurate current controls that are in place, and provide the current baseline of what organisations have at the moment.

We want to encourage all of the organisations using Risk Ledger not just to share this information, do their assessment and move on; instead, we want them to open a dialogue, open a conversation with each other, and support each other to improve their controls.

Rather than using this data to change the way that we do business, we provide it to our customers and the suppliers on a shared platform to give them a baseline to work from while also highlighting certain areas where they might want to dive a bit deeper with the customers and suppliers they’re working with, which can support and improve certain controls that may or may not be in place.